A Writerly Rorschach

Wonderbook Chapter 1: Trust your gut; question your process, and be more playful

Note: This is the first of a seven-part1 summer read along of Jeff Vandermeer’s Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction. Grab a copy of this gorgeously illustrated book and read along with us or simply enjoy the essays inspired by this beautiful meditation on the imaginative life.

Jeff Vandermeer kicks off Wonderbook with the following playful invocation:

If you don’t like the whimsy of that opening, it’s probably best if you close the book and back away, because this amiable tone dominates the pages I’ve read so far. But if you—like me—are charmed so much you leaned forward as you read, then let’s dive in, shall we?

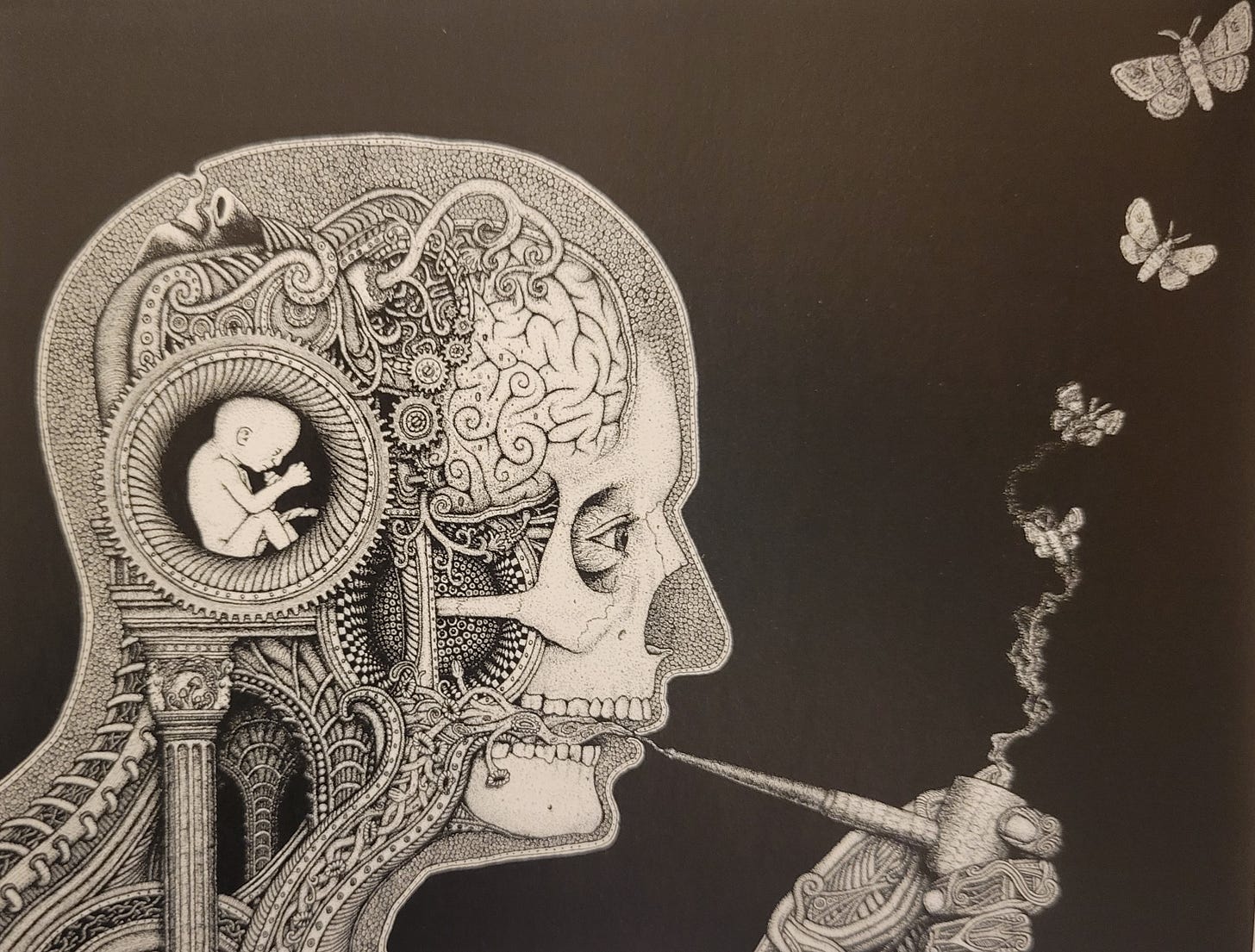

Reading through the introduction and the first chapter of Wonderbook, I’m struck by two things. One, this book is so beautifully illustrated that it’s a crime against art that designer Jeremy Zerfoss isn’t credited on the cover,2 and, two, although Vandermeer says this craft book was intended to be “a cabinet of curiosities that stimulates your imagination,” but the the introduction and first chapter read more like a writerly Rorschach3 test—any writer cracking it open will find the advice they most need for the writer they are at that moment.4

In that spirit, the writing advice that first leapt off these pages for me was Vandemeer’s insistence that writers follow their instincts. And I do mean insistence. In the course of 50 pages, Vandermeer reminds the reader to follow their own counsel no less than six times :

In the first paragraph of the introduction: “And always—always—keep your wits about you.”

On page 2 of the first chapter: “When it comes to your uniqueness and personal creativity, discard what doesn’t resonate with you and use only what makes sense.”

On page 7: “…sometimes you’ll find you need to break free of other people’s imaginations to allow your own uniqueness to shine through.”

On page 39: “Beware of advice from people who say you have too much imagination. There is no such thing as too much imagination.”

On page 40: “Be fiercely protective of your imagination, and nurture it.”

And—I would argue—in the very last paragraph of the chapter: “The imagination is infinite—it can encompass all you want it to encompass, if you let it. Everything we see around us, whether functional or decorative, once existed in someone’s imagination. Every building, every fixture, every chair, every table, every vase, every road, every toaster. In fact, the world we live in is largely a manifestation of many individual and collective imaginations applied to the task of altering preexisting reality. So the question becomes, How can you position yourself to dream well?”

Message received (and received and received and received and received and received)!

A quick confession, though: A public read along of Wonderbook wasn’t my first choice for a summer series for HIBOU. If I had a bit more courage this newsletter would be the first in a series on intuitive writing, but after doing a little freewriting about possible essay topics that series might include, I found that a high percentage of the topics required considerable research, and I got a bit intimidated by the scope of the project.5 But one of the essay topics I brainstormed was trusting my gut as a writer, so clearly I had conditioned myself to pick up on the write-to-the-beat-of-your-own keyboard clicking content in Wonderbook.

That combined with the fact that the message gets relayed six times!

Anyway, watch this space for a series on writerly intuition. Maybe in the fall? Maybe in the winter? This summer, though, HIBOU is all about Wonderbook, and two other pieces of advice covered in the introduction and chapter one captured my attention—writerly fetishes and writerly yearning.

But before I dive into fetishes and yearning (which sound like they’re related but aren’t really), I want to pause to reiterate the idea I shared at the start of this newsletter—that this book truly is a writerly Rorschach.6 As such, I’m discussing the bits that moved me to write while my sleeping puppy snored, but I’d love to hear what in the dense richness of these opening fifty pages resonated for you.

Maybe you enjoyed Vandermeer’s meditation on the cocktail of imaginative inputs and outputs that make us the writers we are.

Or perhaps one of the three delightful quest essays by Rikki Ducornet7, Matthew Cheney, or Karen Lord pulled you in.

For me, Vandermeer’s web extra about discipline was the second thing that made my fingers itch to write. The complete text is here, but the gist is this: Vandemeer cautions against writerly fetishes—his word not mine!—and his list of tools he’s decided were just fetishized procrastination includes (but is not limited to) writing with favorite pens, writing at particular times of day, and writing only after doing specific mental exercises.

Let me just say as a proponent of using mantras to psyche myself up to write in the morning by hand with a rotating crop of favorite pens, I feel attacked.

I also have a question.

Namely, who the hell does this Vanderdude think he is?

A man who can pry my ballpoint pen out of my cold dead hand, that’s who!

But in the second half of the essay, Vandermeer segues into a meditation on the difference between habit and process—habit is something you do blindly because you’ve always done it while process is something you do because it works. Then he defends his own inefficient analog process by saying he needs “the messiness of little notes and scrawled charts because my inefficiency leads to further inspiration.”

If he can’t read what he’s written, no matter—he’ll come up with something he might not have considered if his first choice were legible.

If organizing scraps of inspiration into an outline is unwieldy, it’s worth it—that’s how he discovers the best order of events organically.

“If my process, or anyone’s process, seems ridiculous to you, make sure you’ve tried and discarded it first,” Vandermeer writes. “Also recognize that your response to various processes changes over the years as your writing changes. If you’re stuck on a creative project, it might have nothing to do with having written yourself into a corner. Instead, you might need to change your process. You might even find the solution in a process change you rejected five years before that now works perfectly for you.”

Given I’m a die-hard fan of longhand writing, reading how Vandermeer champions what’s essentially my process should give me the feels—instead it just gives me pause.

Because Vandermeer suggests that if you’re stuck on a creative project, you might consider changing your process. And while I’m not stuck creatively, puppy parenthood means I am stuck with less time to write for the next few months. Where I’d normally write a chapter by hand and type it up in the same week, I’m finding that process is taking two weeks this summer, which is particularly frustrating given my handwriting has a half-life of three days—the longer it takes me to type in a chapter, the less I’m able to decipher my intention, particularly given my bad habit of trailing off after I scribble the first few letters of a word. If I’m typing the longhand draft up the next day, this deteriorating legibility isn’t a problem, but if revising a chapter by typing in takes me a week, whole sentences are often lost.

But it’s not like I can’t draft on the computer.

In the eight months since I launched Hibou, I’ve drafted all my essays on the computer—I’m drafting this very sentence via keyboard, in fact. And, yes, for a few trickier essays, I broke down and printed out what I had to wrestle the draft into shape with the help of a pen, but I can count those pen-assisted essays on one hand.

What if I could draft the last two chapters and the epilogue of my novel-in-progrss directly on the computer? What would I lose?

Traditionally my answer has always been that I’d lose permission to be messy and sacrifice the opportunity to fix the draft as I type—what I like to call my type and tweak draft—but what if the detailed scene notes I have for the ending of my book is rough draft enough?

And, really, what’s the point of tweaking the draft when those detailed scene notes also included detailed revision notes for sections one and two? The changes I make to parts one and two are apt to ripple into the ending, so maybe it makes more sense to leave the drafts rough rather than tighten pages that are basically guaranteed to change.

The part of me that has been writing with a pen since I was a kid is feeling mighty squirrely right about now, but a deeper part of me knows drafting on the computer makes more sense this summer. And if I ever feel like I’ve written myself into a corner, I can always pick up a pen to try writing my way back out.

Because the faster I get to the end of the book, the faster I can get to the real work of revising. So maybe I’ll recognize writing longhand for the habit it is—beloved though it may be—and ask myself to shake up this part of my process.

Lord knows Shiloh has shaken up every other part of my life—why shouldn’t she shake up my writing, too?8

And if drafting on computer saves me enough time, maybe I can even explore my third big take away from these opening fifty pages—a yearning that bubbled up from the combination of Vandermeer’s discussion about the idea that creativity is born from a splinter—that we write either to heal a wound or to fill a yearning—and his challenge that we feed our imaginations by yielding to them as regularly as we can:

“The act of becoming a writer—of committing to learning the craft or art of writing—is largely about providing structure to what your imagination creates and is an ongoing process of attaining an elusive mastery (there is always another door),” Vandermeer writes. “But generating these initial sparks is one of the few parts of writing that becomes easier as you gain more experience—as long as you don’t suppress the impulse. Which is to say, if you reward your imagination by writing down your ideas and exploring them, even the slightest little fragment, your imagination will reward you with a more or less continuous stream of ideas.”

The idea of the wound fueling our creativity isn’t a revelation to me—there’s a reason I tend to write about misfits—but the idea of yearning juxtaposed with the idea of the yields reaped by following your imagination where it leads made me nostalgic for my days as an early writer when I was game to try any class or genre or writing group:

My passion for flash fiction was ignited by my tenure in a writing group so enamored with flash that we published a group flash chapbook.

My interest in screenwriting landed me—and the poor novelist I convinced to take part in my shenanigans—in a screenwriting class where we were delightfully over our heads.9

My up-for-anything beginner approach to writing meant I did a stint as a writer for Grub Street’s newsletter, I contributed to a series of collaborative stories for an interactive project for the Boston Book Festival, and I actually gave short story ideas the respect they deserved by writing them instead of filing the idea away for some time in the future—always the future—when I wasn’t so focused on a novel, but the end of one draft has a way of leading to the start of the next, and those story ideas have a way of languishing in notebooks.

Which is not to say I’m unhappy writing novels—I adore the way a novel allows me to dig deeply into the lives of a motley crew of characters.

But I do miss the playground of my writing life before I got serious about novels.

The way writing short pieces and exploring new genres inspired ideas I might not have had otherwise.

The delight in permitting myself to play.

Which is also not to say I don’t play as I write the novel because I do.

But there’s something about chasing the rabbit of a new idea—a new short idea that can be executed quickly—that’s so much more satisfying than the long game of a novel.

Maybe it’s not that it’s satisfying so much as it’s gratifying.

Instantly so.

I think that’s part of the appeal of writing a regular newsletter. HIBOU functions at least for me as a regular and (somewhat) sanctioned writing outlet that scratches my itch for writerly synchronicity.

In fact, I experienced one of those synchronicities as I was writing this essay. When I went look for a Bookshop link for Wonderbook, Google served up these sponsored hits at the top of the search results:

A nonfiction book about the science of human wonder, an illustrated memoir about an artist, and a novel with a cover so wondrous my heart screamed wantwantwant before I even read a description, after which my heart screamed REALLYWANTWANTWANT!

Before that search I did following the rabbit of this newsletter, I’d never heard of any of those three titles. Now I want to read them all. And I find myself wondering if the next series should be about wonder instead of intuition. Will it be? I don’t know. I don’t even know what a series about wonder would look like, but a rabbit hole is only as good as the questions it makes you ask—if you know the answer immediately the question wasn’t pushing you anywhere near hard enough, right?

So that’s my take away for the first 50 pages of Wonderbook: trust my gut, question my process, and be more playful.

What resonated with you?

Seven or more. These chapters are rich, long, and dense. I may have to split a few chapters across a couple newsletters to do them justice.

I suspect the decision to leave him off the cover might be complicated because there are so many illustrations in the book that belong to other artists. To be sure, Zerfoss is credited in the opening pages as the book as the designer and as the creator of all the illustrations not credited to someone else—and Vandermeer gives him a shout out right in the introduction—but I still think that a book this visually stunning should bear the designer’s name on the cover.

I have given up every hope of ever being able to spell Rorschach correctly without looking it up. My use of the word in this footnote is no exception.

Confirmation bias? Maybe, but I’d argue our very perception of the world is an exercise in confirmation bias. I got a puppy a month ago an suddenly my neighborhood is filled with doggos and dog people when I know realistically there’s exactly one more dog in the neighborhood. OK, three, but I only know that because Shiloh met a pregnant dog who has since given birth to three puppies, I heard through the grapevine. I also heard that two of the puppies were normal wee puppy size and one was a bruiser, but I can’t confirm as I don’t know this woman well enough to knock on her door and ask to see the puppies. And, yes, I did consider it because, well, puppies.

And thank the writing gods I did, too, because there’s no way I could have managed a research project in this, the summer of the puppy. Though, if I’d announced a series on intuition instead of a read along of a book I know a few of you went out and bought, I’d have likely given myself a green light to make this summer series the summer of the puppy, too, which—knowing me—would have turned this into an all-puppies-all-the-time Substack.

Didn’t spell it right in one go that time, either!

Doing a little wiki reconnaissance on Rickki Ducornet, I encountered a word I’d never seen before in the description of her work: Diablerie. Merriam Webster says it means words or pictures representing black magic or—and this is the definition that tickled me—mischievous conduct. And just like that diablerie is warring to knock shenanigans out of my ever evolving top-ten favorite words.

Given that the only content I’m shared on Hibou in the last three weeks is 100 Days of Summer check ins, the argument could be made that Shiloh has already shaken up my writing.