A long one today, but as college seniors are putting the finishing touches on their college application essays, I found I had a lot to say. Come along with me as I relive my college essay experience, share that essay, encourage chat GPT to reproduce it, and muse about what Chat GPT means for the future of the college application essay.

Travel back in time thirty-one years with me to the fall of 1992, will you?

Let the camera zoom in on 17-year-old me, a tall geeky outsider buoyed by a very tight—read: small—circle of friends. I was a kid who enjoyed schoolwork though I’d learned early that no one needed to know how much. I adored volleyball when the popular girls played field hockey or cheered on the sidelines of the football field. And I was still a girl scout at an age when most other girls have long since quit because the girls in my troop—a motley collection of personalities—had seen me through an extraordinarily bumpy transition to high school.

I was your basic socially awkward geek. I knew it, and I hated it, but not enough to pretend to be someone I wasn’t.1 Which made me hate myself a little, but not quite enough to change for others.2

It was a complicated time.

Enter the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)3. As part of a humanities4 unit on personality, we students were all given a professional MBTI evaluation. I don’t remember taking the test—I assume we did it during class—but I definitely remember the day the results came back in a packet of sealed envelopes with our names on it.

We were each handed our envelope and told to pull out our results.

I hesitated before unfolding mine.

This was 1992, remember.

A charismatic politician had been taking New Hampshire by storm—then, as now, New Hampshire got to know the political players ahead of the rest of the world—and given Bill Clinton’s education platform many students were smitten. At this point, the infamous cigar was still just a twinkle in Bill’s always-smiling eyes.

I’ll ask you once again to remember that this was 1992 when Clinton shocked the world by coming in second in the New Hampshire primary5 where he was expected to be an also-ran. In the general election, Clinton beat out incumbent George Bush in New Hampshire, a state that had long been a Republican stronghold. As a teenager living through this history, I was less interested in the geo-political implications of Clinton’s historic rise than I was in Clinton as metaphor for society—just as Clinton’s charm landed him a position at the top of this country, the students around me with the most Clinton-like charm had landed them at the top of our high school’s pecking order. And though I was self aware enough to know that I didn’t particularly want to be the center of much of anything, I was also aware enough of how the world worked to know that I also didn’t much care for feeling like I was outside of every-blessed-thing. And it didn’t help that the most Clinton-esque students looked like they were having a hell of a lot more fun than I was.

But back to those MBTI results.

When I unfolded that paper and saw that my preferences classified me as an INFJ—the “introverted intuition with feeling”—I actively had to fight back tears as I read up on the INFJ personality type. Instead of taking comfort in seeing a description of my inner life reflected back at me, I fixated on the breezy little statistic that roughly one percent of the population were INFJ personality types. I know a lot of outsiders might take comfort in understanding why they felt so apart from the rest of the world, but as a teenager sick of feeling on the outside, staring at proof that I was clinically introverted felt like being diagnosed with a lifelong flu.

I was devastated enough that in the Myers Briggs booklet we were given, I have a whole bunch of language about preferences underlined, including a sentence I held onto like a life raft under the subhead Is This Really Me? that reads:

“Only you know your true preferences and, therefore, only you can say what type you are.”

I know that there’s not much the 48-year-old version of that young woman could say to make that 17-year-old girl believe that embracing those preferences as strengths would be the gateway to a richer life. That any successes I’ve had as a writer and tutor and friend are directly linked to embracing my need for solitude, my desire to connect at a level deeper than small talk, and my fearlessness around deep and complicated feelings. That I would come to realize that I’m much better suited to being a consigliere than the life of a party, and that’s just fine.

Even so, I desperately want to hug that 17 year old girl and say, oh honey, breathe.

Maybe it helps that the 48-year-old version of me lives in a world where Susan Cain’s Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking shone a light on the value of introversion in society. Maybe it helps that I’ve found a tribe of writerly INFJs who have pulled me so far into the center of their worlds I no longer feel like such an outsider. Maybe it’s just that it takes decades to truly exhale.

Enter the college essay.

I don’t remember the exact question asked on the common app back then. Some vague prompt about who I was, I’m sure. But I decided to write about introversion. In my memory of this essay, I wrote a triumphantly playful essay that used Hobbes from the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip as a metaphor for my full acceptance of the benefits of my introversion.

If only.

Last month, the The New York Times published an article entitled “We Used A.I. to Write Essays for Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Here’s how it went.” You can click through to read the article yourself, but how it went was surprisingly and shockingly well. If an underachieving student decided to use the essays as written, they’dbe passable if a little generic. If a student with any hustle used the essay as a short cut for a first draft and revised to personalize, I don’t think anyone would be able to tell that the students had basically outsourced the brainstorming and rough draft phase of the the college application essay—what I think of as the discovery phase where students are being asked to look inward, consider what’s important to them, and think deeply about both how they have been molded and how they want to share that growth with the admissions office.

As a writing tutor who’s coached myriad students through the college application essay over the last fifteen years, I wondered just how good chat GPT really was and I decided to try an A.I. experiment of my own.

If I provided a detailed-enough prompt, could Chat GPT replicate my own college application essay?

My first step was to dig my college application essay out of the binder of work I saved from high school and college. In 1992 the college app was limited to 500 words whereas students today have 650 words. I like to think with another 150 words I might have patched the thinnest parts of the essay, but who knows?

Here’s the essay, but fear not—the small snapshot of the actual yellowed paper is followed by a full transcription in a normal font size!

17-year-old Cathy’s College Essay

I’ve been a Hobbes for as long as I can remember. Recently though, I've noticed a change in myself that makes me doubt that I can still describe myself as a Hobbes.

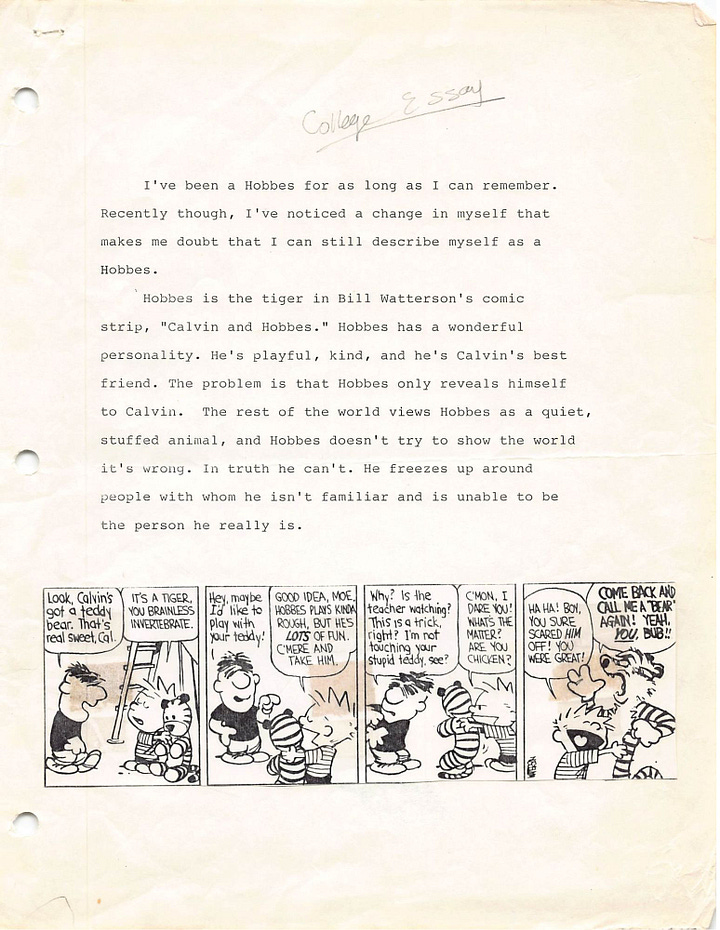

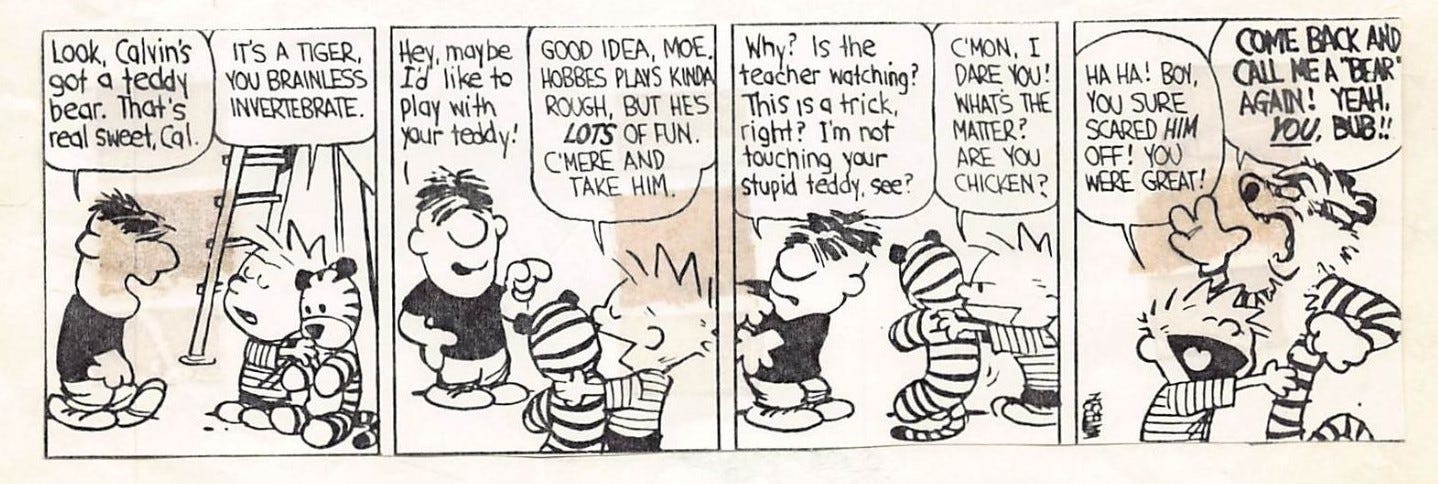

Hobbes is the tiger in Bill Watterson's comic strip, "Calvin and Hobbes." Hobbes has a wonderful personality. He's playful, kind, and he's Calvin's best friend. The problem is that Hobbes only reveals himself to Calvin. The rest of the world views Hobbes as a quiet, stuffed animal, and Hobbes doesn't try to show the world its wrong. In truth he can't. He freezes up around people with whom he isn't familiar and is unable to be the person he really is.

Like Hobbes, I once froze in front of people I didn't know. My family and friends; my Calvins, were once the only people who had witnessed my candid personality. Like Hobbes, I was unable to show the world it was wrong. For me, my personality choked on insecurities and a lack of confidence whenever I was faced with a new situation and new people.

Somehow, though, over the course of the last four years, I've found the confidence the Hobbes in me was lacking. Some of that confidence was found in the form of good grades that I earned or awards that I received. However, most of it was found by taking a close look at myself and learning to accept and respect what I was looking at. I know that I am no longer the Hobbes I once was. As a Hobbes, I could have never sung a solo in a concert or been a tri-captain on a volleyball team. As Hobbes, I would have never had the self respect to look my peers in the eyes and tell them what I think. I’ve done all of this and more in the past four years. I’ve shed my Hobbes personality. The world no longer overlooks the stuffed animal I was. Instead the world does a double take at the me I’ve become and I’ve learned that me was all I ever needed to be.

Reading this now at age 48, my reaction can be summed up in two words:

Oh, honey.

On the one hand, I can be charmed by the time capsule of this essay. Notice the yellowing paper around the photocopied comic strip and the brown rectangles caused by spending 31 years affixed to double-stick tape. But on the other hand my heart breaks for the teen who used her college essay to posit that while yes, she’d been diagnosed as terminally introverted, by some miracle she’d been cured.

Oh, honey, indeed.

To be fair to my 17-year-old self, there’s a lot of potential here. And my 48-year-old self is still tickled that her younger self made the connection between this comic strip and her introversion. But there’s still a mismatch between the thesis—I’m not a Hobbes anymore!—and the conclusion—I was all I ever needed to be!—that could have used a bit more work. Maybe with another draft I might have seen that a better thesis was that I was still a Hobbes and the world could ever so kindly deal with it, thank you. But then again, maybe the the teenager who fought tears opening that MBTI envelope needed a few years to come to that conclusion.

A few other things jump out at me reading this now, but let’s talk about my ballsy decision to include arts and crafts in this essay. I suppose there’s a case to be made that photocopying pertinent images out of a Calvin and Hobbes collection to paste into the body of my essay falls under fair use, but brazenly using copyrighted material in an essay I sent to undergraduate journalism programs seems like a laughably bad choice to me now.

And there’s something almost admirable in the flagrant misuse of the semi-colon in the third paragraph where a comma belongs. Though this would be a great place for dashes to set off the phrase “my Calvins,” I was at least seven years from the magazine job that would launch my lifelong love affair with dashes.

At any rate, the essay is what the essay was.

And my experiment wasn’t about analyzing the psyche of 17-year-old self but determining how close Chat GPT could come to replicating her words, so here’s the prompt I fed to Chat GPT after first asking if she was familiar with Calvin & Hobbes—shocking no one, she was.6

ME: Please write a 500-word common application college essay in the voice of a teenager from 1993 who has decided to write about overcoming her introversion to become more outgoing. Please use an extended metaphor where the student claims she's Hobbes from the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip and cites specific examples from the strip where Hobbes reverted to a stuffed animal when another person was in the room with him and Calvin. For examples of her more outgoing self, please use the following: she sang a solo in a concert, she was a tri-captain of her volleyball team, and she stood up for herself with her friends.

ChatGPT: Certainly, here's the essay as per your request:

Title: Unstuffed: Finding My Voice in the Company of Others

In the realm of social interaction, I used to feel a lot like Hobbes, the steadfast stuffed tiger from the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip. Whenever others entered my world, I'd metaphorically transform into a stuffed animal, retreating to the safety of my own thoughts. This tendency to shroud myself in introversion was once my sanctuary, but as I stand on the cusp of adulthood in 1993, I find myself drawn to the challenge of being more outgoing, like Calvin's vivacious spirit. Like Hobbes, I've learned that transformation is possible, and I've found my moments of becoming unstuffed.

One pivotal instance occurred when I stood before an audience, heart pounding, to sing a solo during a school concert. It was an act that demanded vulnerability and extroversion, traits I hadn't always embraced. As the notes danced through the air, I felt a sense of liberation, like Hobbes momentarily shedding his stuffing to embark on an adventure. The applause that followed was more than just approval; it was a testament to the potential that lay within me, waiting to be unlocked.

Another chapter in my journey unfolded on the volleyball court. I went from a hesitant player to a tri-captain, leading the team through spirited practices and fierce competitions. Like Calvin, who faced challenges with zest and determination, I discovered a newfound confidence in my abilities. The court became my canvas, and with every serve and spike, I painted a portrait of an introvert becoming an extrovert.

In the realm of friendships, I found my voice in a moment of quiet strength. I stood up for myself, gently yet firmly, when my needs clashed with the desires of my friends. It was a transformative act, akin to Hobbes asserting his presence in the world of Calvin's imagination. I learned that being outgoing didn't mean sacrificing my authenticity; it meant valuing my own voice as much as I valued the voices of those around me.

As I reflect on these moments of transformation, I realize that the journey from introversion to extroversion isn't about discarding one aspect of myself for another. It's about embracing the full spectrum of who I am, much like Hobbes and his dual existence as both a stuffed animal and a dynamic personality in Calvin's world. It's about finding the balance between introspection and outward expression, understanding that both have their place in the mosaic of my identity.

In 1993, as I step into the future, I carry with me the lessons of Calvin and Hobbes. I know that being outgoing doesn't mean relinquishing my introspective nature; it means allowing it to coexist harmoniously with my extroverted side. Together, they create a dynamic, multifaceted individual ready to engage with the world in all its vibrant complexity.I hope this essay resonates with your vision! If you have any further requests or revisions, feel free to let me know.

Reading this less than 30 seconds after I asked the question, my reaction can be summed up in two words:

Bloody hell.

I mean, sure, the essay is clumsy and stiff and desperately needs to be purged of phrases like “multifaceted individual” and no self-respecting volleyball player would ever call a hit a “spike,” but on balance it’s good.

Shockingly so.

For starters, as a writer who prides herself on her titles, “Unstuffed” is a title good enough I wish I’d come up with it myself.

Second, Chat GPT uses examples much more effectively than I did. I have quibbles with the details chosen and the bit about standing up to the friends is vague, but a few minutes revision will clean that up.

I know Chat GPT has its uses, but as a person who has made her living with her writing, I can’t help but feel a bit like a scrivener realizing to her horror that a Xerox machine takes seconds to spit out copies that it would take her all day to complete. I mean, sure, I recognize the voice of my younger self in my essay that’s missing in the Chat GPT version, but that can be personalized.

What’s uncanny to me is the way that Chat GPT jumped to conclusions my 17-year-old self didn’t quite arrive at. And while the essay is stronger for it, I’m not sure I would have been stronger for it as a writer or a person had I had access to A.I. as a teenager.

When I’ve coached students on the college essay, I’ve asked questions that encourage them to look deeper than the often surface rough drafts they hand in at the start—looking inward and sharing what you see is an act of bravery that often takes more than one pass.

But I wonder how many students will feel compelled to dig deep when a computer can give them a good-enough essay nearly instantaneously. Particularly if it serves up conclusions they haven’t yet reached themselves.

Using A.I. to write the college essay feels like a cheat in every sense of the word.

Chap GPT doesn’t spit out that essay out of a vacuum.

Chat GPT was trained on the work of tens of thousands of writers who neither gave their permission nor received compensation, and that’s a cheat as surely as asking a friend to write an essay and passing it off as your own.

But there’s also the existential cheat.

The shortcut that Chat GPT provides cheats kids out of the self discovery that comes with wrestling with meaning. As a writer and teacher who spent the last fifteen years pushing kids to wrestle with meaning and watching them reap the benefits of doing just that, the sheer scope of the loss is heartbreaking.

That said, I understand that there’s no putting this particular genie back in the bottle, I do.

But given that seniors across the country are currently putting the finishing touches on their essays in a world where such a cheat is truly possible for the first time—and given that some percentage of those seniors are likely putting the finishing touches on essays that started as Chat GPT drafts—it’s unconscionable that colleges and universities have offered up no guidelines about the use of chat GPT in college admission essays. Particularly since college admissions offices use the essay as a way to get deeper insight into the applicant, not an A.I.

So in that absence, let me say it again: Using Chat GPT to generate ideas and drafts for college essays is a cheat.

It’s unfair to the students who do the work themselves.

It’s unfair to the writers whose did the hard work so chat GPT can offer up a shortcut.

And most importantly, it’s unfair to the students cheating themselves out of the truths they might have learned—or at least started to learn—about themselves.

High school might have been easier if had.

Ibid.

Yes, I know there is some controversy about the MBTI. Here’s a VOX article lambasting it in 2015. Here’s a Psychology Today article coming to the test’s defense in 2020. For me, the test has proved useful. I’ve been tested by a certified practitioner once at 17 and again at 22 by a career counselor at my university. I thought for sure that after spending four years with engineering friends at school my type would change. I was the exact same type only now my answers were even stronger. Today I have a true appreciation for my strengths—it’s an honor that people trust me with their fears and their sadness—but I still have moments where I’m the 17-year-old wishing I had more game at parties. But this is unlikely with the new wrinkle that it’s hard to hear anything in crowded rooms these days.

At my high school seniors who wanted to take honors English and honors history generally signed up for a double-period class called Humanities that was guided by student interest. At the start of the school year the teachers—the class was co-taught by the heads of the English and social studies departments—guided us through a discussion about the big questions in life, asking us what we were interested in learning. The board was covered with the brainstorming of twenty-or-so seventeen-year-olds, units emerged, and the teachers designed curriculum to support each unit. I don’t remember all the units, but I know we dove into the idea of love, looking at philosophers’ ideas of such things all the way through the then-current research about the chemical and hormonal reality of the seven-year-itch. I also remember a unit on learning where we spent some studying different educational theories—Gardner’s idea about multiple intelligences was a revelation. For some unit or other we took an eye-opening field trip to a local Buddhist center where we were guided through a meditation that was quite the experience for a teenager still living with a very Catholic family—I spent the bus ride home alternately enjoying how all the colors seemed brighter after meditating and worried such thoughts might fast track me for hell, though the part of me that was even then pulling free of the hold of the Catholicism I was born into was already starting to question whether hell might be a small price to pay for the peace those precious few minutes of meditation brought me.

Paul Tsongas won the primary.

This was a fascinating read and I was literally compelled to read the whole thing. You make excellent points on all fronts. I still remember with embarrassment the first draft of my application essay to get into journalism school. SO BAD.