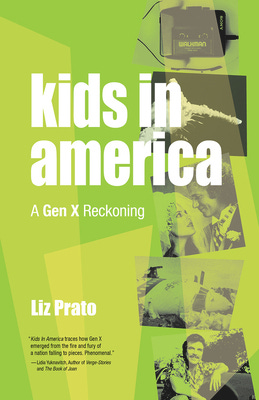

Our February Tenacity Tale is Liz Prato, author of Baby’s on Fire: Stories (Press 53, 2015),Volcanoes, Palm Trees, and Privilege: Essays on Hawai'i (Overcup Press, 2019), and Kids in America: A Gen X Reckoning (Sante Fe Writer’s Project, 2022), an unflinching essay collection that “reveals a generation deeply affected by terrorism, racial inequality, rape culture, and mental illness in an era when none of these issues were openly discussed.”

Try to remember the last time you were ill. Go back to the day you could barely move your limbs. The day you didn’t want to—or couldn’t—get out of bed. The day you despaired that you’d ever feel like yourself again.

Now imagine that you never did.

Putting three books out into the world in seven years is a massive accomplishment for any writer, but Portland writer Liz Prato did it while living with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), an illness more commonly known as chronic fatigue syndrome.

“In 2013, I got sick with a cold that turned into bronchitis, and I never really recovered,” Prato says. “I’ve never really been the same person since.”

Because ME has a shockingly long list of symptoms, the lived experience of the disease is particular to the individual patient, but one symptom most patients share is bone-deep fatigue that’s exacerbated by the kind of light physical and mental effort that healthy patients take for granted—showering, dinner with friends, reading. Other symptoms include muscle and joint pain, brain fog, and dizziness.1

Prato wasn’t diagnosed until 2016—three years into the illness that changed her permanently—and even then, she had to push her primary care doctor for the diagnosis. 2

Living—and Writing—with ME

Before the illness, Prato adored being a fit person. She ran. She hiked. She lifted weights and kickboxed.

And that’s just who she was physically.

She was also a powerhouse in her literary community who attended myriad readings, volunteered to guest-edit literary journals and anthologies, and traveled to conferences.

“I taught two classes a week independently,” Prato says. “I wrote freelance articles while working on a novel and seeing massage clients four days a week. And I still had energy to see friends and hang out with my husband.”

Now, most of those things are out of reach without intense modifications. Last month, for example, Prato co-taught a series of three one-day “pop-up publishing” classes on Zoom with Laura Stanfill, the publisher of Forest Avenue Press, a format that accommodated Prato by sharing the load, allowing her to work from home, and limiting the scope of the class to a focused subject—a class on querying, say, instead the wide and sweeping writing topics that tend to crop up during a traditional writing workshop.

“I can’t even be part of a regular weekly writer’s group because I wouldn’t be able to do much else,” Prato says. “I’ve had to reprioritize everything. And there is a lot of things that don’t make the cut that I wish made the cut.”

So, what does make that cut?

Socially, Prato prioritizes her husband and loyal friends.

Financially, she prioritizes projects that pay. “I really don’t like how hard it is to make money since I got sick,” she says.

And artistically, she prioritizes writing. Because she regularly has reliably less brain fog and more energy between 10:30 a.m. and noon, Prato uses that time to shower and write, but doing so comes at a cost—Prato must rest an hour for every hour-and-a-half to two hours of work or risk a crash.

During a complete crash, it’s hard for Prato to lift her hand, even just to feed herself, and when she does lift her hand, it’s tiring to chew. And yet Prato considers herself lucky because even during a full crash, she can walk if she holds onto things and shuffles along. Other folks with ME can’t even get out of bed.3

The Energy Envelope

So, writing makes the cut, but other literary endeavors have to be chosen carefully.

“There’s a lot of free labor folded into being a good literary citizen—showing up for things and looking over this essay or chapter or blurbing this book—and that has ableism baked into it.”

For a writer living with ME, completing such an exhaustive list of tasks isn’t even possible.

If there’s an event Prato wants to be at—a launch for a dear friend, say—it’s not just a simple matter of noting the date and time of the event in the calendar. She also has to minimize her other commitments for the the day of the launch and consider her schedule not only for the day immediately before the launch—so she’s not too exhausted to attend—but also for the day immediately after the launch in case attending depletes her completely.

“Before I say yes to something, I have to ask what I’ll get out of it—will I feel fulfilled by this interaction?” Prato says. “I hate that this sounds weird and selfish, but I have to think of it like an energy envelope—there’s only so much energy in that envelope, and it doesn’t magically replenish overnight. Not for me. So, I have to ask myself how long will I be tired after I do this? and make choices.”

Working on Our Own Timelines

Healthy writers could learn a thing or two about holding space for their work from the medically necessary boundaries set by writers with ME.

Where many non-fiction writers sell a book based on a proposal, Prato always finishes her books before shopping them so she can work on her own timeline, a healthy concept all writers might do well to consider adopting. Ask yourself where you might be compromising your ideal timeline to meet someone else’s.

Do you really want to race through 50,000 words in November or are you only doing it because a persuasive writer in your circle said participating in NaNoWriMo would be a rush?

Do you really want to get feedback on a chapter of your novel every week, or are you only doing it because your writing group’s submission schedule demands it?

Are you chatting with the other soccer moms at practice when you’d rather pop into that coffee shop across the street and get a little work done?

And while Publishers Weekly has trained us to think that a multi-book deal is the gold standard, isn’t it possible that the crushing deadline expected for a contracted book—with the added distraction of the editing and publicity work to support the first book—is a devil’s bargain?

Say Yes and No Mindfully

Also consider how your timeline is compromised if “yes” is your default answer to every literary request that comes your way.

“I’ve had to reconsider what literary citizenship looks like because I can’t get out to all the events I used to,” Prato says, “so much of what I do now to support other writers is done from the computer—publicizing events I can’t go to, posting pictures of people’s books.”

If we say yes to every book that comes knocking for a blurb, every manuscript a friend wants you to read and critique, or every article in a prestige publication that wants to pay your in exposure alone, you’re actually saying no—or at least not yet—to your own priorities for the time it takes to complete that request.

Which is not to say that we can’t make time for the literary favors that feel like a genuine joy:

Maybe you’re at the start of your career and building up karma by being as involved as you can.

Maybe you have a found family of writer friends that you’re happy to say yes to again and again.

Maybe you’ve got a book coming out that you want to share as widely as possible, so you’re saying yes to a high volume of requests even though doing so means saying no to the new idea vying to be your next passion project.

The key to saying yes without growing brittle is threefold:

Be aware that saying yes is a tradeoff. The first step to saying yes with joy is understanding that there’s a cost to doing so, even if it’s a cost you’re happy to pay.

Be intentional about what you say yes to. Before you say yes, think about your own energy envelope and make a plan for how you’ll clear space for the work you’re taking on.

“When I sign a contract for a book, I have to consider all the hustle I’m expected to do—social media, events, conferences—and plan it out,” Prato says. “Because writers with chronic illness don’t have the ability to do the hustle—not all of it anyway. We just can’t.”

And if saying yes would spread you too thin…Say no. You may have always said yes to requests from that writer who feels like family, but when you’re on deadline for a publisher—or even if you’re “just” honoring your body’s need to get to bed early instead of staying up to finish notes on your friend’s new chapter—remember that no is a complete sentence.

“While I always encourage grace, kindness, and gratitude, I also don’t think we owe anyone an explanation for saying no,” Prato says. “It’s not our responsibility to make it easier on them. Being disabled is hard enough without worrying about ‘Gosh, have I been nice enough about protecting my health?’”

And because it bears repeating, remember: No is a complete sentence.

Break the Compare and Despair Cycle

Another simple way writers can conserve their energy is by opting out of the temptation to compare their progress to the progress of others. Because if it takes everything you have to write for some small window of time a day—because you’re chronically ill, you’re working a full-time job, or you’re the primary caretaker for a child or an elderly parent or both—what possible good can come of chastising yourself for not keeping pace with the twenty-something-year-old writer who pumped out a book while she was on full scholarship to a graduate program that paid her a stipend to live?

The answer is none.

No good can come of such a comparison.

And if you find yourself chronically making these kind of hurtful comparisons, get the hairy heck off social media for a month or two…hundred.

What it boils down to, though, is this—it’s critically important to offer grace to your writing self.

“I plan my energy for life, and writing is an incredibly important part of my life,” Prato says. “Somedays I might be too tired to write, and that has to be OK.”

The opening paragraph of Kids in America

We were privileged We were mostly white, although a few of us were Black or Hispanic or Asian or Native American. We were old money and new money and not a lot of money, but the majority of us were upper-middle class. In movies and TV shows that depicted schools like ours, the kids drove BMWs and Mercedes and Porches and Corvettes. We drove brand new Jeeps and Jettas, used VW Rabbits and hand-me-down station wagons. Some of us didn’t have cars, so we bummed rides from the ones who did, or from our parents.

Order the book here!

The opening paragraphs of Volcanoes, Palm Trees, and Privilege

The most fascinating detail I learned on my first trip to Hawai’i when I was twelve years old is that the Hawaiian alphabet consists of only thirteen letters. For many years I considered this a profound metaphor about Native Hawaiian’s organic wisdom and simplicity: while white Americans needed twenty-six letters to prattle on about our lives, Hawaiians managed to say everything they needed to say in only thirteen. To express love, war, land, water, hunger, birth, thirst, fire, family, death—all they required was a, e, i, o, u, h, k, l, m, n, p, w, and the mysterious ‘okina.

It wasn’t until well into adulthood—after over a dozen trips to the Islands—that I realized these thirteen letters were not endemic to the Hawaiians. These letters exist because white Americans assigned them to represent Native Hawaiians’ oral communication. Prior to Western contact, the sole written language of the Hawaiians had been petroglyphs: simple but evocative drawings of waves and warriors, volcanoes and rain, turtles and sharks, carved into rock. This can be seen as a primitive form of communication, or as evidence that story is art, and art is story.

Order the book here!

The opening paragraph of Baby’s on Fire

Three months after I graduated from Colorado College, and things weren’t going well. First, I couldn’t find a job. It’s like I was expecting a salaried, corner-office job, either. In this economy, with a liberal arts degree, I knew better. But I couldn’t even get my ass hired at Starbucks.

Order the book here !

Tenacity Tales is HIBOU’s monthly celebration of the tiny tenacities in a writerly life. If you have a tenacity tale you’d like to share, comment below or send me your pitch at hibou@substack.com. To learn more about what we’re looking for, read the original Tenacity Tale here.

Subscribe to HIBOU for regular—and free!— content about writers on the hunt for the wise (and wisecracking) writing life!

For more information, read the CDC’s series on ME, including myths, symptom management, and guidelines to support patients.

For more information on the medical community’s recent change of heart where ME is concerned, read Chronic fatigue syndrome estimated to affect 3.3 million in U.S. Also, take a look at The New York Time’s February 21, 2024 article about findings from NIH’s seven year study of a small sample of patients with ME/CFS, the first study to demonstrate notable physiological differences between healthy bodies and bodies with ME/CFS.

For profiles of other writers living with the disease, read novelist Jennifer Acker’s essay on Oprah Daily or Paul Costello’s 2016 interview with Laura Hillenbrand in Stanford Medicine Magazine.

There is so much I love about this Tenacity Tale, Cathy. The 3 lessons are key to a happy writing life. Adhering to them can prevent heartache, agita, and FOMO. Those tenets allow for joy where there would be guilt, and better time management because you're not ruing what you are not doing. Thank you for this gift.

I've come to these tenets myself, but over many years of trial and error, ruing and saying yes to things I wish I did not. One rule I've developed: instead of feeling I have to do everything possible for a writer friend launching an essay or a book, making sure I do one thing for those I care about and considering the rest gravy. Buying the book, reviewing it, attending the launch, promoting it on social media, even just recommending it to friends or requesting it from the library helps. Seeing that list as a menu instead of an obligation has brought the joy back to my literary citizenship.

Thanks for this post, Cathy. So many important nuggets here. And hats off to Liz for managing to do all that she does despite such a major obstacle.